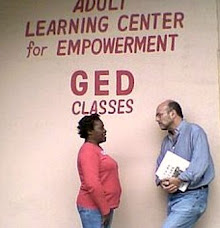

(We at SVDP-ALC are very happy to welcome our next guest writer, Robert Burch, Ph. D. If the name sounds familiar, that is because you read about his father at our blog at our July 19th post about World War 2. I first met Robert when we were students at Jesuit High in New Orleans, and we stayed in contact via mail and email over the years. He now lives up north with his wife Mary, who is also a Ph. D., and their children. He is still very interested in New Orleans and especially the state of education in post-Katrina New Orleans. He has been following our school's blog and has advised me many times on scientific aspects concerning our Antarctica project. After Jesuit, he went to college at Tulane University in New Orleans and then graduate school in chemistry at the University of California at Berkeley.

(We at SVDP-ALC are very happy to welcome our next guest writer, Robert Burch, Ph. D. If the name sounds familiar, that is because you read about his father at our blog at our July 19th post about World War 2. I first met Robert when we were students at Jesuit High in New Orleans, and we stayed in contact via mail and email over the years. He now lives up north with his wife Mary, who is also a Ph. D., and their children. He is still very interested in New Orleans and especially the state of education in post-Katrina New Orleans. He has been following our school's blog and has advised me many times on scientific aspects concerning our Antarctica project. After Jesuit, he went to college at Tulane University in New Orleans and then graduate school in chemistry at the University of California at Berkeley.I asked Robert the following question: Why should someone want to study science? This is the key question for our students. And here is his reply.

-- Adrian)

The Wonders of Science

By Robert Burch, Ph. D.

Do you ever wonder what makes things tick? For example, why do seeds sprout? What causes your heart to beat? What is a rainbow? Why are the days longer in the summer than the winter? All of us have a natural sense of curiosity about the world around us to one degree or another. That’s the stuff of science. It’s the study of the natural and physical world around us, so that we can make it understandable.

I remember a special moment I had early in school. It was in science class, and the teacher taught us about simple machines. There are six of them – pulleys, levers, wedges, incline planes, wheel & axle, and screw. The teacher showed us that examples are all around us, both in manmade machines and in the natural world. It was an Aha! moment for me, because of two things the teacher did. She showed us that complicated machinery is often nothing more than a careful assembly of lots of simple machines. This meant for me that complicated things could be understood in simple terms. Once again, it was the stuff of science.

I remember her teaching us about “mechanical advantage”, which was using basic arithmetic to figure out how much benefit these simple machines could provide in carrying out a job. For me, this was an inkling that science could be used to advantage in real life situations in ways that we could precisely define before even doing the job. It meant that science not only satisfied my curiosity but could be made useful to make people’s lives better. You can call that the practical application of science, or “technology”.

The practical application of science translates into all sorts of arts and crafts and trades we do in the adult world. It’s the basis for things. For instance, if you are a boat welder, how do you know what kind of material to use to weld the joint or what temperature? It comes from science. If you are a painter, how do you know what kind of paint to use for a certain job? It depends on using the right scientific formulation for the conditions the paint is exposed to. If you are a health care worker, how do you know when you’ve provided sanitary conditions for your patients? You use the scientific knowledge you have of how and where germs grow. As a consumer, how do you know what consumer information to believe? You apply the basic science you learned to the consumer product and how you intend to use it.

The sense of wonder and the practical application of science in everyday life, those are the reasons to study science. I made a career out of science, but you don’t have to make it a career to get a lot of benefit out of studying science.

(Thanks, Robert, for helping our students better understand the importance of science. Yes, a knowledge of science is especially important in the technological world of today; and, as our Antarctica project has shown, science can be fascinating and fun to learn too. -- Adrian)

No comments:

Post a Comment